Harvest

Human hair has long been treated as a curious kind of crop – easy to grow but difficult to harvest. In the nineteenth century rural women all over Europe sold their hair in exchange for money or trinkets. Today most hair is collected from India, China and other Asian countries where large numbers of women still have very long hair and many are poor enough to think of selling it. Once cut, it is used as material for wigs, hair extensions and eye lashes which are sold worldwide and form part of a billion dollar global industry.

Dried, Koppal, India 2013

Bleached, Chennai, India, 2013

Puffed, Mandalay, Myanmar, 2015)

Street market, Yangon, Myanmar, 2015

Street market, Yangon, Myanmar, 2015

Street market, Yangon, Myanmar, 2015

Mother selling daughter's hair, Brittany 1900

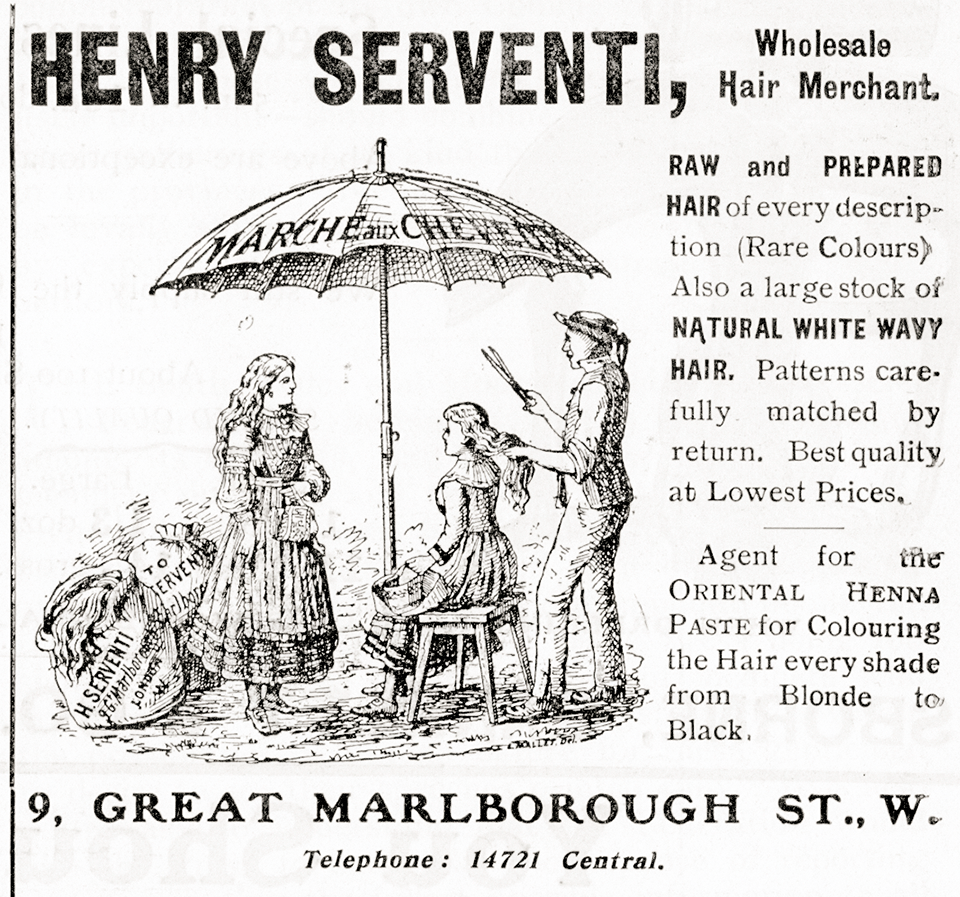

Hair advertisement, 1912

London hair merchant, 1909

Politics and Trade

Hair has long been caught up in global politics and commerce. Poverty, political events, religion and fashion all effect supplies.

Chinese Entanglements

When men were forbidden from wearing long plaits (known as ‘pig tails’ or ‘queues’) in China after the 1911 revolution, this boosted supplies of hair for European fashions but when the United States introduced a ban on imports of hair from communist countries in the 1960s, hair traders turned from China to India in search of supplies.

Forced hair cutting by Chinese revolutionaries, 1911

Chinese revolutionaries cutting plaits, 1911

Mockery, desire, hypocrisy on willow pattern plate

Times of War

German WW1 posters calling on women to sacrifice their hair for the fatherland. The hair was used in submarine engineering. © Imperial War Museum.

Donations

In many religions cutting and shaving hair is an act of humility, self-sacrifice and devotion or a way of thanking or pleading with God. In the 19th century ‘church hair’ was collected from Catholic convents in Europe and used for making wigs and hair pieces. Today the Hindu pilgrimage site of Tirumala in South India is famous for its tonsure halls where 650 barbers are employed to shave the heads of pilgrims who have come to fulfil their vows. In Myanmar (Burma), thousands of women have had their heads shaved to raise money for building bridges and repairing roads. In renouncing their hair, they follow the example of the Buddha who renounced worldly attachments. These altruistic offerings of hair are sold by auction into the hair trade.

By offering hair, people offer something of themselves. Today charities like the Little Princess Trust invite people to donate their hair for children with cancer and alopecia.

Buddha renounces his hair

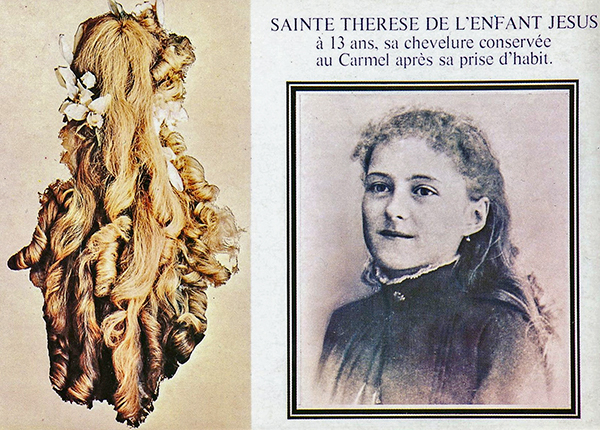

The Hair of Ste. Therese, offered at the time of becoming a nun.

Human hair rope made from hair offered by followers and used for the rebuilding of the temple in Kyoto 1895.

Tonsure, Pallani, India

Frankie offers her hair to the Little Princess Trust.

Combings

We shed between 50 – 100 hairs a day. In many parts of the world long haired women collect up the combings that accumulate in their brushes and sell them in the form of matted hair balls. These combings can be upcycled and are commonly used for making the cheaper range of hair extensions and wigs. Forking waste hair balls out of the gutter was once the job of street pedlars in Europe. Today there are hair peddlers all over Asia who travel by foot, bicycle, motorbike, boat or bus, gathering waste hair door to door in exchange for small gifts or petty cash.

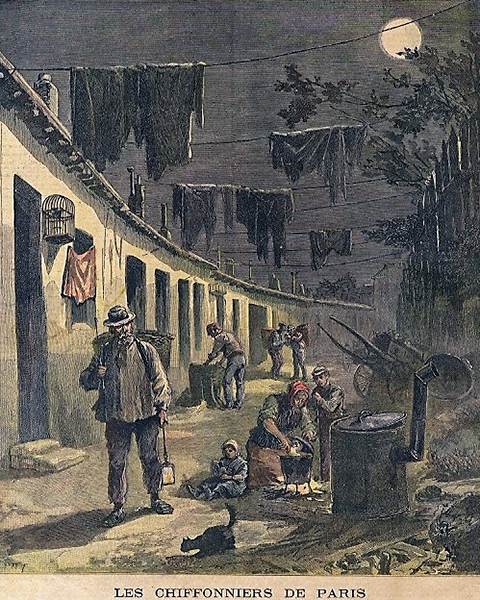

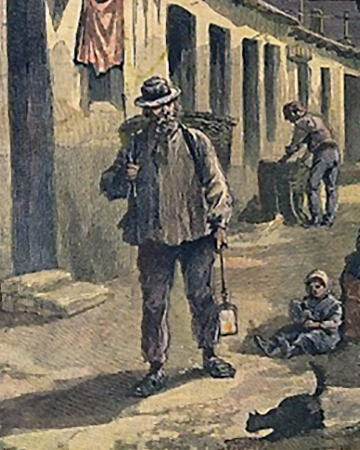

With a basket on his back and a hooked stick, the rag and bone man worked at night, hooking tangles of waste hair out of the open drains. Paris, 1892

Ragman preparing to hook hair out of the gutter

Chignons for supplementing bobbed hair, Paris 1925

Street collector, Chennai, India

Combings workshops, Mandalay, Myanmar

Hair Receivers

Once a recognizable component within ebony vanity sets, the hair receiver was an extension of the nineteenth century's obsession with hair. A small lidded pot with a finger-sized hole; it was designed to house loose strands extracted while brushing. The resulting mass was made into 'ratts', potato-sized bundles stuffed, shaped and sewn into hairnets, and worn beneath the owner's hair to create volume and height. It was, of course, a perfect match…

Today vanity sets are as uncommon as the dressing tables they once adorned, and solitary hair receivers are mistakenly resold as ink or pencil pots.

Hair Receivers is a mélange of ebony artifacts, unscrewed and reconfigured into new ensembles. An unlikely harmony of dissenting parts, they are seemingly purposeful, yet without apparent function.— Jane Hoodless

Jane Hoodless, Hair Receivers, 2017

Jane Hoodless, Hair Receivers, 2017

Personal combings