Hair Stuff

Tabitha Moses’s gleaming Hairpurse is a striking reminder of how human hair is fetishised, sexualised and commercialised. Today the Internet abounds with websites selling hair and bears witness to the range of wigs, extensions, eyelashes and other products available on the market, whether in London, Lagos or Los Angeles. History reminds us that this global trade is nothing new. When hair becomes attached to new heads it becomes incorporated into new life stories, offering possibilities of protection, transformation, fashion, beauty and disguise. Reborn on different heads, hair takes on new meanings.

Tabitha Moses, Hairpurse, 2004

Factory-made wigs, Korea, ca. 1970

Hair products for sale in a London shop

Re-personalisation

If wigs could speak, what stories would they tell?

I may look natural but I’m actually synthetic. I was made in China and bought in London for £20. But I’m still beautiful and proud of my natural look.

I’m made from combings but my owner doesn’t know it. She likes me because I am 100% human and have a fine lace front and because I give her the straight hair she’s always craved.

I spend most a lot of time under the bed. My owner bought me when she was diagnosed with cancer. She chose me because I looked like her own hair but when her hair fell out she didn’t feel like wearing me. She was more comfortable wearing scarves but I like to think I accompanied her through a difficult period.

My owner only puts me on when he is alone in the house. But he promises to take me out one day. I can’t wait and I plan to look sensational!

I’m a little tired but I’ve been revamped. My owner is a married woman from an orthodox Jewish family. She never leaves the house without covering her own hair. I like to think I am more glamorous than her hair underneath!

Human hair wig

Head moulds

Templates for American male hair pieces, made in China

Wig blocks showing scars of travail, Raoul's, London

A Brief History of the Human Hairnet

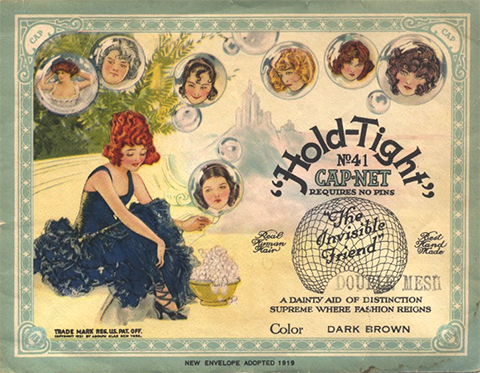

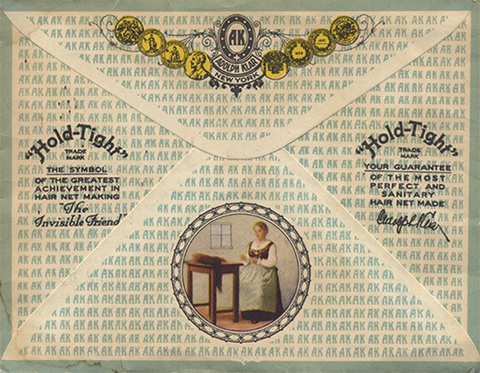

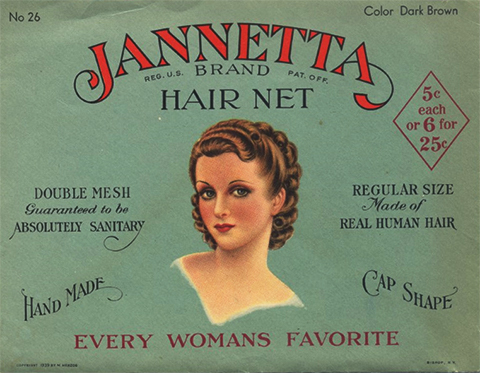

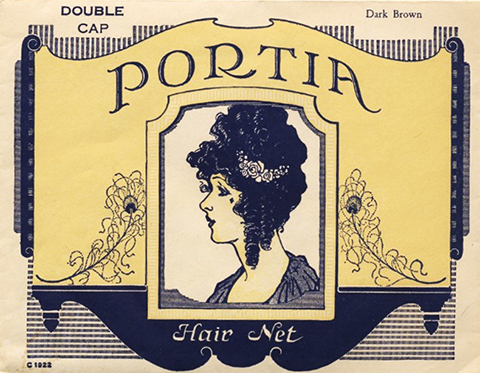

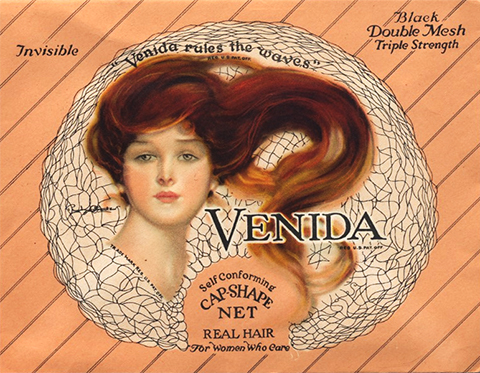

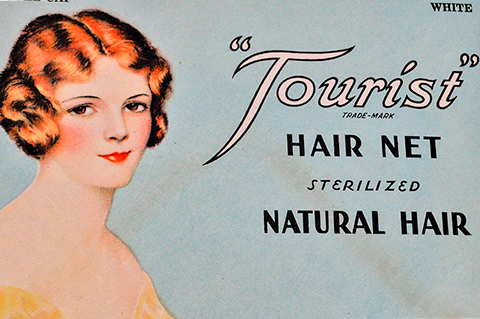

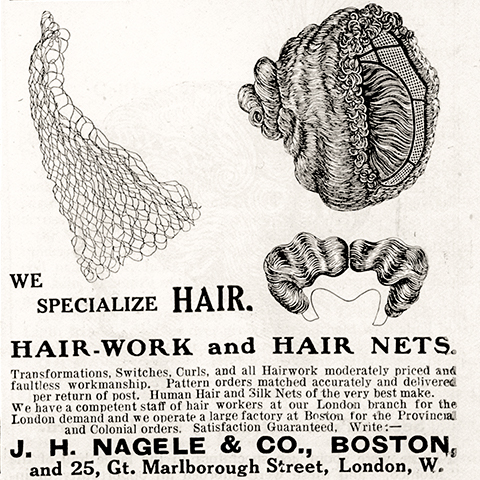

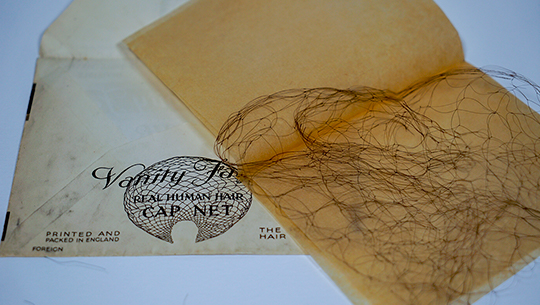

In the first half of the 20th century a trend developed for hair nets made from human hair. This delicate work of hand-knotting was performed by poor women and children in Alsace, Bohemia and later China.

Only Chinese hair was considered strong and flexible enough for making hairnets. This lead to a hypocritical situation in which Americans mocked the Chinaman for his ‘pigtail’ whilst simultaneously coveting his hair for their hair nets. Ladies of fashion in Europe and America preferred not to know too much about the origins of the hair in the packets, fearing that they might catch diseases from it. Companies preferred to put emphasis on the fact the hair was ‘sterilized.’

Hair nets were made either from combings collected from men’s plaits by local barbers or from whole plaits which flooded the market in the years around the revolution of 1911.

The Alsatian peasant woman dressed in her finest Sunday best, demonstrating hair net making in Selfridges represents the front stage of the industry. Backstage as many as half a million Chinese women and children were employed making hairnets for the Western market when the fashion was at its height around 1920. But fashions are fickle. With the advent of nylon the global demand for human hair nets plummeted.

Satire

Alsatian peasant

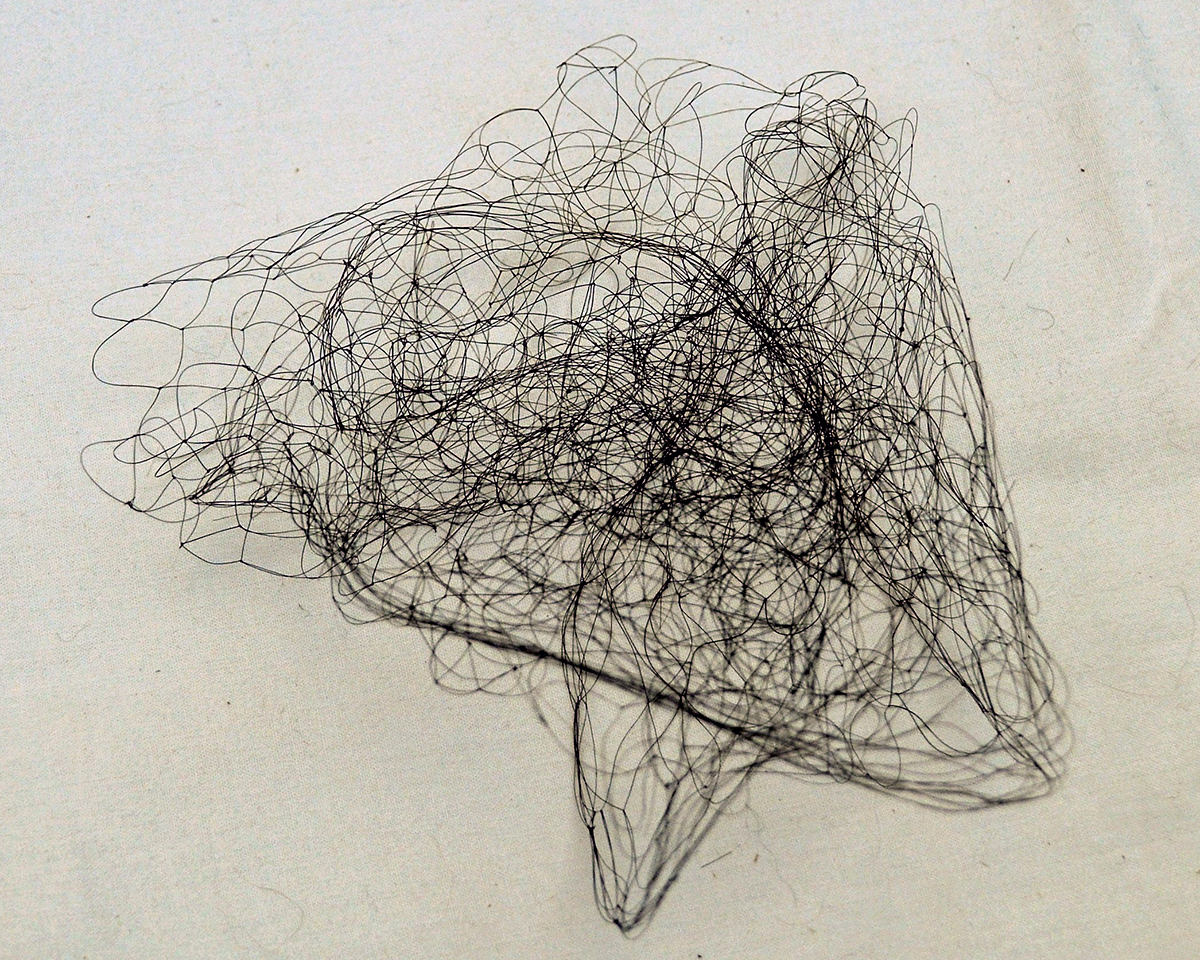

Collection of hairnets hand-knotted with human hair, 1910-1940

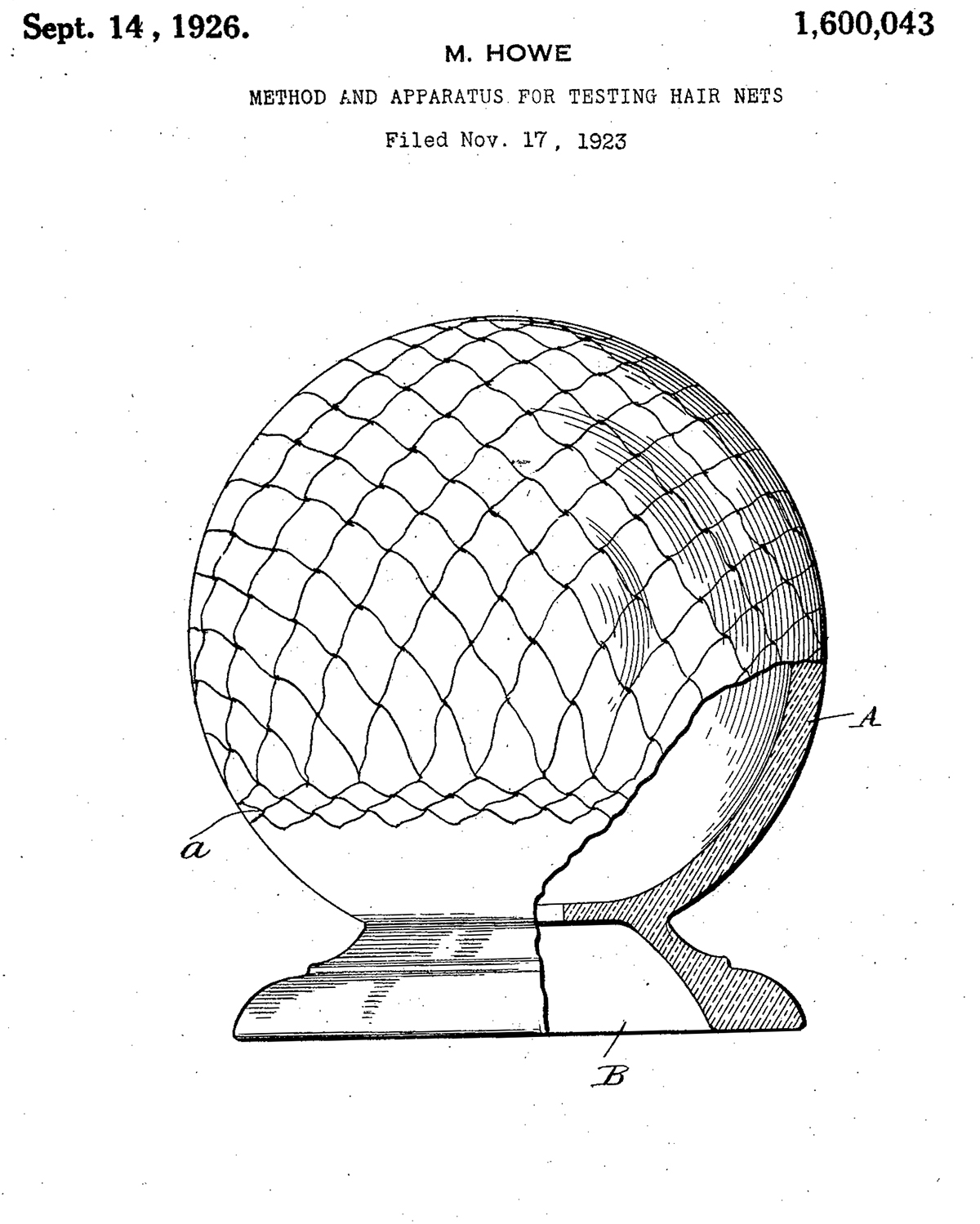

1926 patent for apparatus and testing of hair nets.

Bale of hair